Agriculture

Europe had a huge agricultural business, albeit heavily regulated by the food commission. Most of the production was corporate, heavily automated farming, but a good amount of it was still somewhat manual and even managed by smaller farmers. This trade still allowed a good number of people to work and live outside of the hyper-urbanized European cities. However, it is tricky commerce. Regulations and quotas made it complicated, weather was unpredictable, pollution was high and if you were not one of the big ones, margins were low.

The war itself and the post-war did not make it easier for business. The destruction and disruptions of the war, damaged and destroyed innumerable crops, fields, and greenhouses, but the worse came after the war finished. As mentioned before, during the early years the outlands heated and violence and crime were common, and something as basic as food sources was, for sure, a common target.

The last nail in the coffin for many enterprises was the atmospheric effects from where the time of the red gets its name. The decreased lighting for the crops, the altered rain patterns, the increased pollution, and the blood rain contaminants destroyed years’ worth of crops.

As one would expect, the bigger players with their higher profit margins and mass-produced cheaper crops survived and adapted with biotechnology, but the same could not be said for smaller producers. This was not planned by the bigger corporations and governments, but they did intentionally leave them without support. The intention was, of course, consolidation: Taking their lands and customer base.

The result of this was, for one side, the worsening of quality of food, and for the other availability of cheaper food. The reason, in some cases, was justified, as faster to grow and more resilient food was necessary, especially during the early years, but for most, the goal was simply profit. Getting rid of better quality competitors allows not only to get land for low prices and access to new markets, but also to lower the standards. If there is no affordable availability of better quality produce, customers just have to settle and take what is available.

Asphalt jungle

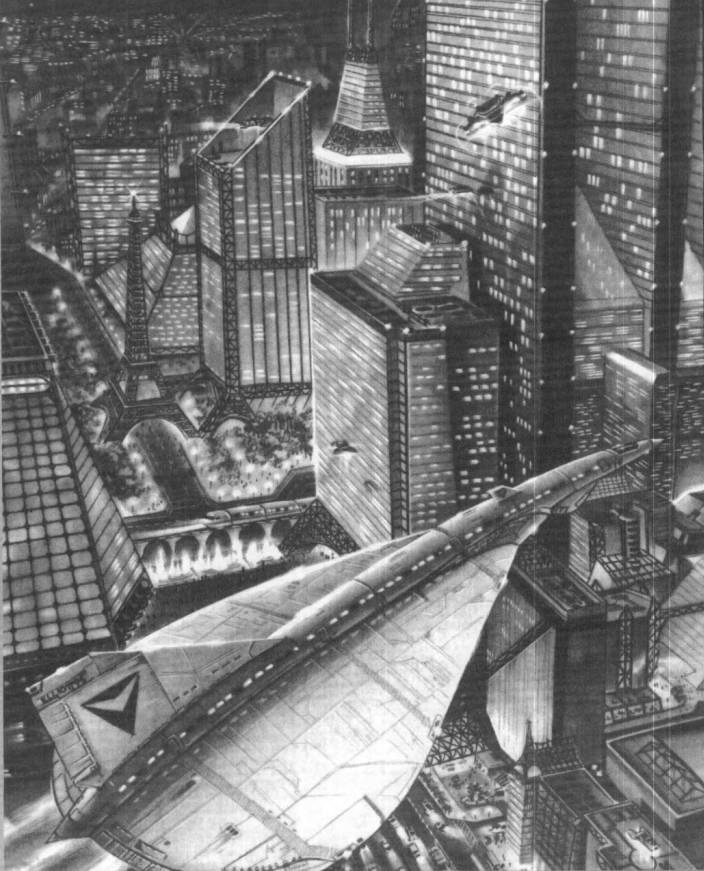

Europe is a very urbanized continent, with over 90% of the population living in developed areas. The cost of land in the developed areas is quite high, causing the way the residential areas form. Except for affluent areas, most European cities’ density is very high, going around the thirty to forty thousand habitants per square kilometer. The lack of space is such that most residences are not single-story, apartment blocks are very common, and even houses tend to be two or three stories to allow them to have more space in the less land possible. It is quite common for suburban areas to be purely comprised of apartment buildings. Such density causes a lack of service distribution, especially for energy. Brownouts and power cuts are common, obviously more often to poorer areas.

The situation worsened with the increased flow of new residents resulting from the 4th corporate war, the datakrash, and the conflicts in Spain, Italy, and Greece. Around ten million citizens were displaced due to the violence in the southern countries, and the weakening of the borders caused by the datakrash added a constant flow of illegal immigrants, mainly from the NCE countries, the hostilities in the outlands exiled several hundred thousand, and the loss of farm work destroyed innumerable communities. The already over-populated core countries could not absorb such a landslide of immigration.

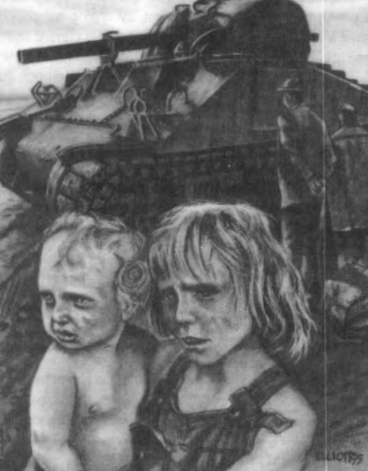

The core countries tried their best to expand residential suburbs, but the rate with which new settlers arrived could not be handled in the best of circumstances, which was not the case after the 4th corporate war, of course. With efforts and resources tied in the rebuilding of the infrastructure of basic services and the creation of new production facilities, urban development was certainly not on top of the list. The outcome of it all was the birth of many makeshift dwellings, or at least intended to be makeshift. Refugee and illegal camps sprawled around almost every major city. The conditions in these camps were atrocious, in the best of cases you’d get some container housing and in the worst a tent. Energy access was scarce, sanitation facilities were shared and limited, and employment was unexistent.

This was, of course, a ticking time bomb. Most of the displaced, refugees and illegals were poverty-stricken, had limited or no knowledge of the language of the country they moved to, and close to no contacts or support. Particularly during the early years, the food and subsistence the governments could provide were limited, so hunger, illness, and idleness were rampant with desperation and anger slowly brewing. As it was to be expected, crime grew and gangs formed, one more violent than the previous. The Organitskaya and the mafias, noticing the potential, started wars for the territories while recruiting the locals.

Noticing the situation, the governments tried to improve conditions in the ring camps (turns out that resources become available once things turn dire). With collaboration between construction firms and the nomads, many suburbs sprawled, even mega-buildings were made. Food distribution eventually normalized, employment formed, and some integration programs helped many to learn the language. However, the damage was already done. Not every outer ring camp became crime-stricken, but between scarcity, lack of policing, and the feeling of alienation that already built in some new outer areas became very dangerous or full-out combat zones. Combat zones were not unseen in the core countries, but they were relatively rare. This has changed, some say permanently; Europe might not go back to what it was.

New principalities

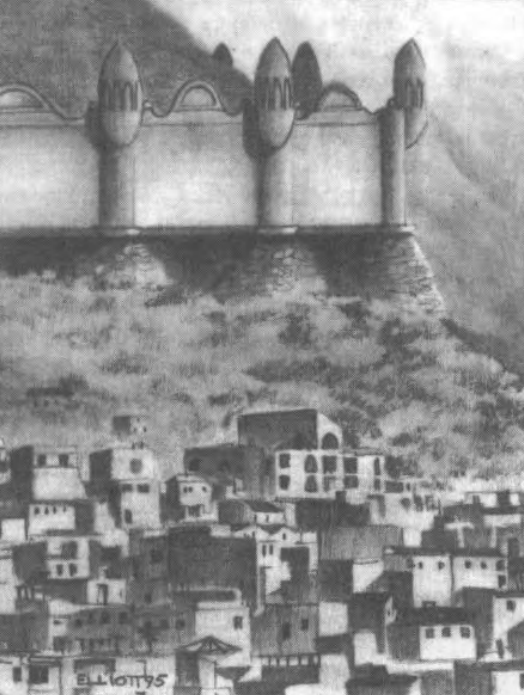

The core countries, with the tremendous influx of population, did their best and absorbed as many refugees from the European conflicts as they could. They even ended up taking many illegals, although not intentionally. But others would not dare try to join the cities, could not join the cities, or would not join the cities. Those who did not took their eyes to the outlands. Several joined either gangs or nomad workgroups, but others dared and took to the pioneer life.

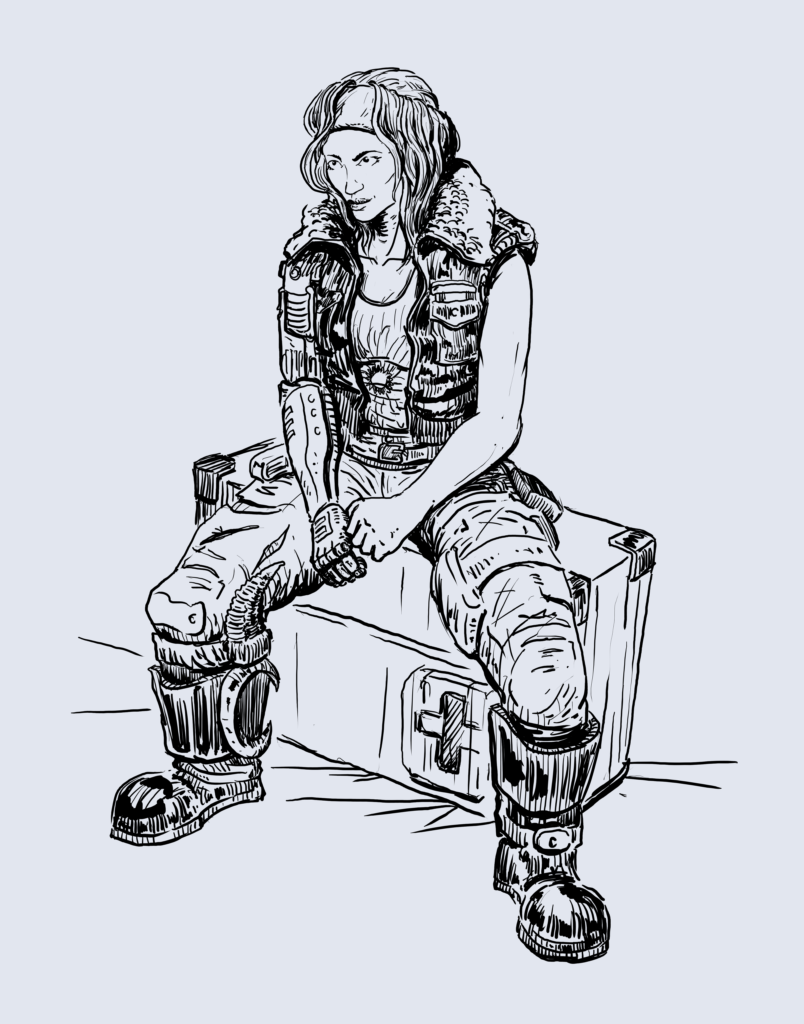

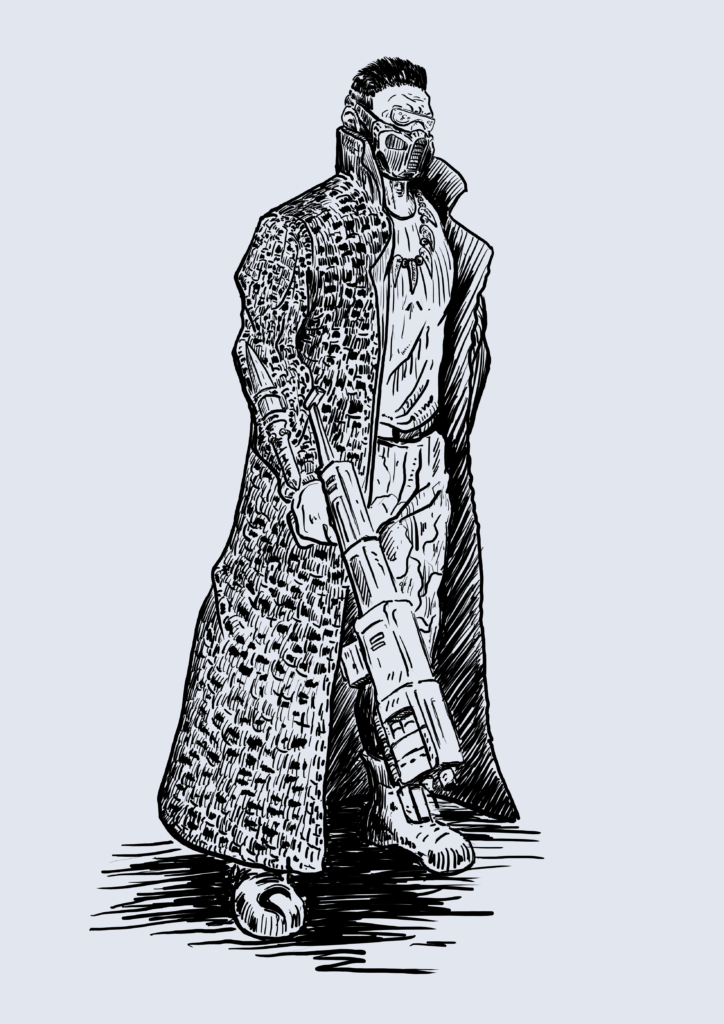

With the abandonment of many towns in the rural areas of the core countries, illegals, gangs or just those who reject authority took over abandoned towns and made them their homes. The level of urbanization and comfort of those towns varied, from being more than a campsite to a populated trading post and rest stops for the nomads. These towns became interesting experiments on alternative forms of organization and leadership, tiny ecosystems where the edgerunner life thrived openly in a way that could rarely be seen in Europe. Techs with shops and businesses offering their trade from electronics to weaponry and cyberware, or even establishing energy production and maintenance services; Medtech shoppes providing discreet services and products with inventory that could compete with any Scandinavian clinic; Nomads and fixers bargaining in goods that would surely land you in jail in a matter of minutes in any European city; solos and lawmen providing security and hired muscle, with weaponry on display that would have raised eyebrows on the grimiest of solo bars in the worst area of Amsterdam.

The Spanish conflicts

Spain was trouble waiting to happen. A country stuck in the past, losing opportunities to progress one after the other, heavily dependent on the EC and their influx of money, and on the edge of economic collapse. A number of natural disasters, corruption, mismanagement, and poor decision-making from the government added to the ravages of the war and the datakrash spearheaded the fragile situation into absolute chaos. Madrid leadership has been fighting a war on multiple fronts, with several but equally dangerous groups resisting their commands and actively trying to depose them.

¡Bietan jarrai!

The Basque country is an interesting place with an unique culture. Strongly attached to their language, history, and society, some of them resist being governed by others than themselves. Having their culture and language denied for decades and being brutally repressed and murdered during the Franco dictatorship, many basque citizens believed they should become a nation with different degrees of independence wishes. The peak of such belief was the Basque National Liberation Movement and their paramilitary forces, ETA, Euskadi Ta Askatasuna. Violence, contempt, and death were the language of ETA, with kidnapping, executions, and extorsion being common. ETA, aware of the fact they were on the losing side numbers wise, exploited terror and violence as a way of keeping the Guardia Civil at bay and achieving their political objectives, being ill-famed for showing no mercy to anyone, irregardless if their opponents actively worked against them or simply were bystanders refusing to support them.

Conflicts reached a peak with the basque conflict during the late 50s and continued in heated conflict until 1998, when the earthquake in the Bay of Biscay almost destroyed the Basque country, in particular the coastal areas, including Bilbao, with giant tsunami waves hitting them. Since Madrid and the EC supported them thoroughly to recover, the separatist movements declared an indefinite truce.

This truce only lasted until 2007, when it came to light that funds originally assigned to the reconstruction of Bilbao were redirected to pay for the Madrid summer Olympic games. During the opening ceremony of the Olympic games, ETA struck again after a decade: a terrorist attack with a grenade launcher directly to the tribune where the royal family was. The attack left 12 casualties, with King Juan Carlos I and other members of the royal family among them. Felipe VI, next in the succession, survived the attack unharmed.

This played right into the hands of the growing ultra-nationalist parties who were yearning for an enemy to unite against. An immense, coordinated propaganda campaign created a strong anti-basque sentiment, giving the nationalists more parliamentary seats and power. Hate crimes, segregation and resentment multiplied against the Basque people and culture, pushing the population further into more radical positions against the Spanish. In response to the propaganda, support for separatism among the Basque population skyrocketed and ETA recruitment multiplied. To make matters worse, Madrid militarized the biggest Basque cities with the help of the army and the Guardia Civil. Bombings, terrorist attacks, ambushes, raids, kidnappings, murders, and all-around violence became the rule in the Basque country and Madrid with constant fights between the ETA and other paramilitary forces against the Spanish forces and anyone that would oppose them.

As a consequence of their own discourse, the Spanish forces became increasingly more aggressive against the pro-independence movements, returning to a level of tyranny reminiscent of the dictatorship. Once again, over-policing, small but cumulative disruptions of day-to-day life, hate, stifling of political dissent and silencing of culture became part of the picture for the basques. As time passed it spiraled out to police brutality, torture, vanishing of protestors and political leaders, unjust prison, and even extrajudicial executions. In turn, this radicalized not only ETA but common people against Madrid, increased ETA attacks, which in turn divided more of the country against the basques and so on, keeping the feedback loop going further and further.

Segona Renaixença

Since the first Catalan renaissance, Catalonia has been in a process of cultural and artistic resurgence that permeated Catalonian society and made New Barcelona and the surrounding cities a preferred destination for the Europan elites, artists, and bohemians. This second renaissance not only improved Catalonia culturally but brought investment to the region and many new businesses to cater to the elites, making it quite wealthy. Environmental awareness, efficiency, urban planning, progressivism (or a perception of it), and technocracy became core values of their society and were heavily pushed in public planning. Barcelona Nova is one of the best and more modern cities in Europe, with the newer and wealthier sections being architectural marvels in an amazing balance between urbanization and nature, but inequality is rampant in the city. The old Barcelona, where the regular workers inhabit, is in disarray, prices are almost inaccessible, and is crime-filled, almost to the brink of being full combat zones.

A new economic nobility grew from the local tycoons who, raised in the influence of the Catalonian nationalist movement, had a really strong nationalism ranging from pride, through separatism, all the way to pure supremacy. The Catalonian government, the local elites, and even some corporations and European regulars funnel money and resources to several of the armed organizations that fight again against Madrid’s control but do so in a concealed manner and do not openly rebel against Spanish influence. They do not want to raise the same attention the basques brought to themselves and want to keep the image of utopia that Catalonia has in the eyes of Europe, so their revolt against Spain is done under the hood.

¡Viva España, Viva el Rey!

Even before the terrorist attack during the 2008 summer games, nationalism was strong and having a rebirth since the 2000s, but nothing is stronger than otherness. The nationalist parties were, mostly, neutral to the royal house. They did not speak against the crown, but surely were not royalists either. The killing of Juan Carlos I, however, gave them the opportunity they needed to find a reason to rally the Spanish population around. The first step was the martyrization of Juan Carlos I, a display of sadness and anger for his murder, and a concerted suspension of every vid display in the whole of Spain to only show the mourning of the deceased king. The second step was the idolatry of Felipe VI, he was thoroughly trained for public appearances; the vid became a propaganda machine displaying every single aspect of the royals’ life in the best of lights, always reminding of the tragedy of the loss of his father and other family members. The final, and most effective of the steps, was the propaganda campaign against the basques. Exaggeration, disinformation, and information bombardment of every single action the separatists made, regardless of it being violent or not, was broadcasted 24/7. ETA provided the nationalists ammunition to keep the propaganda machine going, with their own broadcasted executions and violent messages being used to prop up the hate against the Basque population. Tonnes of entertainment were made either showing basques in a mocking jester manner or portraying them as extremely violent, explosive, criminal, and, in general, in the worse way possible.

The theatre worked astoundingly. The “Mi España” coalition took over the parliament, most community presidencies, and mayoral offices. After an emotive and charged vid appearance by the new king calling for “the rule of law” to be reinstated, the nationalist coalition passed several authoritarian laws classifying almost any anti-governmental sentiment as terrorism and proposed an unprecedented military intervention of the Basque country. The army and the Guardia Civil took over the streets of Bilbao, Vitoria-Gasteiz, and San Sebastian and Bermeo. Protestors, initially peaceful, resisted the intrusion of the military forces but were brutally repressed. Martial law was called to justify violence, hundreds were killed. As was expected, ETA and the other paramilitary forces responded with equal aggression. Raids and bombings were coordinated against forces in the Basque Country, and terrorist attacks and mass shootings were carried out around Spain, but mainly in Madrid. The conflict escalated continuously ever since, although most of it, from the separatists, came as guerrilla and terrorism, and from the side of the Spanish forces, as raids, with little open conflict. However, repression and abuse became a daily routine to the basque population, which worked the opposite to what Madrid expected, raising discontent and dissidence.

The polarized discourse and violence also radicalized pro-monarchy groups. The most active and largest of them were the Monteros de Espinosa, a radical, loyalist paramilitary militia who call themselves the real defenders of the crown. They zealously show up and fight whenever any demonstration against the crown or the nationalist coalition, find and harass basques living outside the Basque Country, and the most radical chapters formed camps in the Basque Autonomous Community, armed themselves, and fight with ETA and the other separatist militias. The Monteros de Espinosa was not formed by the nationalist parties nor are officially supported by them, however, the Spanish forces ignore their actions, silently let them out whenever arrested, and turn a blind eye to them altogether.

Eco-Radicalism

Environmental activism had been common in Europe throughout the 20th century, with groups ranging from neo-pagans, some nomad groups who believed urbanization defiled mother nature to more regular environmentalists. Activists were peaceful, with a few radical groups attacking mostly facilities with little to no harm to personnel.

In 2016, a group of eco-activists staged a protest at the Basque touristic resort at Bermeo, where a corporate conference was being held. Tensions were high, this is the basque country during a tense time in the conflict with ETA. Security was on edge. It is not clear what detonated violence, but the result is remembered clearly today. Corporate security killed 127 eco protesters that day, protesters that were peaceful, that were not armed.

The tone of the ecological movement shifted since then. Environmentalists carried weapons whenever protesting and traveling, not openly, but commonly. Violence, aggression, and vandalism became commonplace during protests and demonstrations, and ecoterrorism appeared and worsened as years passed.

The big collapse

Spain was constantly on the edge of economic collapse, depending on subsidies from the EC and cash-strapped altogether. The 4th corporate war and the datakrash did not do any favors for the world economy, but it treated particularly worse to the Spanish economy. As the EC countries were focused on recovering themselves, income and subsidies steeply declined, leaving the country on the edge of bankruptcy.

Spain managed for years to keep the corporations from buying them off, especially when Agro-corporations wanted to get as much land as they could from the southern European countries. Whether that was deliberate or simply because of poor management, opinions differ. At the end of the 4th corporate war, European countries heavily regulated megacorporations taking advantage of the damage made by Militech and Arasaka. Spain, being desperate, saw the opportunity to survive by, in summary, selling out. They became a corporate haven by giving carte blanche to corps for any dirty business they could not do in the rest of Europe (And Brussels was happy to turn a blind eye to have that produce flowing into the core countries): Borderline illegal research, heavy pollution, low pay resource exploitation, anything as long and they brought money in keeping the Spanish economy from collapse.

The Andalusian banditry

Spain is, in reality, two countries. The cities and the rural areas. The cities maintain some level of richness with the money from the EC and with the poverty from those further away. The south of Spain was the starkest example of the poverty that devastated one half of the Spanish reality. Once somewhat productive with tourism and agriculture, it now lies with unemployment and poverty all around. Tourism died after pollution and radiation destroyed the Mediterranean from the Middle East meltdown, and agriculture was torn down between the great drought in 2013 and the cut to the agriculture subsidies to funnel the money to cities and the remaining touristic areas.

One region of the south had it very harsh: Andalusia. The 2013 drought turned Andalusia into a desert, completely killing their agricultural business. Such a sudden loss plummeted the Andalusians into the highest unemployment Europe has seen. With no resources and help, Andalucia laid dormant for years, just surviving in a suspended state. After the collapse, one corporation saw the potential for profit in the region: Biotechnica. They had the technology to continue agricultural exploitation with little water and an inhospitable environment, and being that few corporations had interest in such an arid place, they gained concessions to exploit the region easily. This was a slap to the face of the Andalusians, Madrid profited by selling their land to the corporations with no benefit to the people, so, once again, as they did many times before, the Andalusian rose, tired and indignant against Madrid and Biotechnica.

Unlike armed insurrections in other regions, Andalusian banditry was disorganized and decentralized. Groups formed, disbanded, and were murdered constantly. Their intentions varied intensely also, from Robin Hood-like figures to murderous road gangs. Most of the time gangs stayed out of each other way, respecting each other territories, but of course, when push came to shove, they fought each other as much as they fought on the roads. There was an enemy they fought even more often and intensely: Biotechnica, their security, and the Guardia Civil.

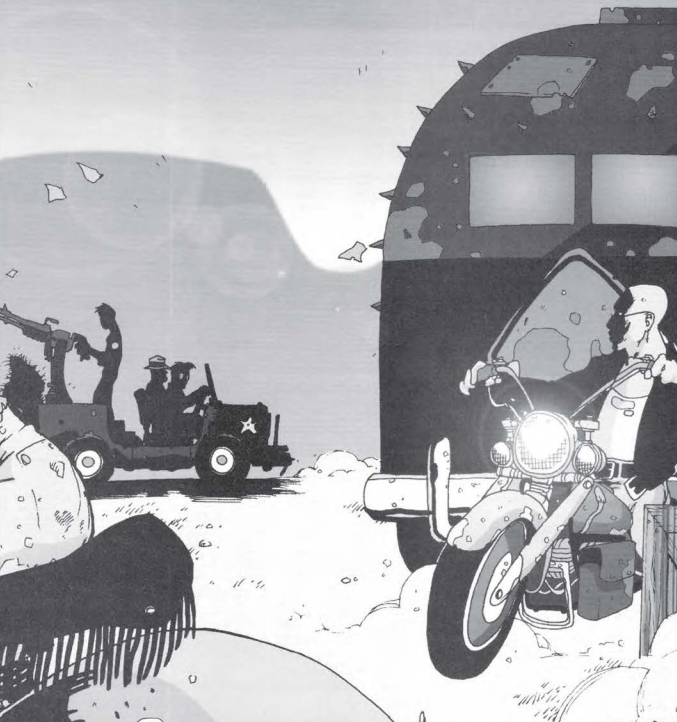

Bandit’s activities varied. Some groups pillaged, murdered and extorted the locals (these lasted little), others dedicated mainly to smuggling, and the rest stole from the government and the corporations, specially Biotechnica. The methods of the latter were very similar to those of highwayman and road gangers: ambushes, raids, sneakily stealing from facilities, taking advantage of the terrain and knowledge; a hit-and-run approach.

Securing agricultural facilities to the size that Biotechnica farms have is a titanic task by itself, but certainly the bandits made it multiple times more challenging. Fighting against many groups that do not coordinate, about which you have no information and who have little to no intel about each other, who the local population aids and defends, and have full knowledge of the area is an impossible task. Aside from the most incompetent or despised groups, most bandit gangs escaped capture and just kept on stealing and disrupting Biotechnica. The more successful bands had a symbiotic relation with the citizenry. They provided food, goods and even health and education, and the population in return protects them, hides them, and is the recruitment pool for the gangs. The feedback loop between prominence, difficulty to capture, and growth rate kept the bigger gangs becoming bigger and harder to destroy. The gang provides to the locals; the locals hide them and join them, with their increased size they take more and smuggle more and the loop carries on.

Banditry did not form in response to Biotechnica acquisition of the Andalusian land. It was growing years before that. Despite that, it cannot be denied that banditry multiplied since then, and got a new focus. The indignation caused by the sale gave the bandits some sense of legitimacy to themselves and the population; it seems like retribution when you take arms against and steal from those who have stolen from you.

Europa Sur has a good relationship with the Andalusian bandits. The bandits, with their control and knowledge of the south of Spain, are an irreplaceable piece in the chain of transport of smuggled goods and provide stolen goods they can sell elsewhere. In the other direction, Europa Sur gave the bandits access to any untraceable materials they might need and money from the smuggling business.

The nature of the conflict between the bandits and the Biotechnica forces was unlike the conflicts against the Basque separatists. Where conflict with ETA was open and violent, most bandits were not aggressive more than when aggressed against or when raiding or ambushing. To Biotechnica this mattered little, as losing equipment, crops and personnel was still major, so they kept pressuring Madrid for support and to act against the bandits. To the government it was also vital to keep Biotechnica in good graces, so they allocated as many forces as they could from their starved forces to unearth and capture bandits, with little success most of the time.

Another side of the conflict that the Madrilenian government tried to fight is the image the bandits have in the collective mind. It’s difficult, even with the propaganda machine, to portrait the Andalusian banditry in the same light they shown the Basque separatism. The rate and kind of violence was not the same. The bandits did not attack the rest of Spain in any major way and a lot of media was still fresh on the Spanish mind depicting the bandit as a hero instead of a villain; A champion of the poor against tyranny and a government that has forgotten them. That did not stop them from trying, but their success was even lower than what little success they had against them in actual hostility, and many in Spain see them with nostalgia and longing for a better time.

Escalation of conflict

Spain, after the fall of the Franco dictatorship and the 1973 oil crisis, began a process of industrial readjustment where most of the mining extraction and processing reduced or stopped altogether. After the 4th corporate war, however, the need for basic resources in Europe rose enormously, and, with global distribution disrupted, there were few places where to get materials to fuel the reconstruction. Being in a critical economic situation, in conflict with the basque separatists, the Andalusian banditry, the rising eco-terrorism, and Europa Sur, the government had to get funding fast.

Mining and processing is not a cheap process in such a place as the EC and environmental protections make it even costlier and difficult. The Spanish government, seizing the opportunity, gave resource extraction in concession to corporations and, to make it cheaper, scrapped safety and environmental laws. In another situation, the EC would not have allowed breaking EC laws in such a blatant manner, but being in need as they were, they silently let it slide.

Several areas of Spain, specially economically depressed ones, got their lands given in concession for resource extraction. Andalusia, Murcia, Valencia, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque Country and Navarre had most of the mineral resources and got most of those reserves sold. Many in the local population were quite thrilled about all the business brought by these new opportunities, oblivious (and propagandized) about the consequences. Some other areas, however, were resistant to having their communities polluted and sold for cheap.

The Basque country and Navarre had been historic regions with reservoirs and exploitation of iron and copper, so when time came the government did not hesitate to give away contracts for them. This was the last straw that broke the camel’s back for ETA and the separatists; seeing their resources and money spent and taken from them once again by Madrid, now with added injury as disease and corruption of their homes and people. Seeing their money stolen when they most needed it in 2007 and that same land they refused to rebuild being sold infuriated the basque people and pushed the radicals further away.

As accidents, disease and pollution became more evident, more basques became fanatical and militant and joined either ETA or eco-terrorist factions. Attacks and battles became bolder and open, Spanish force or sympathizers were brutally murdered and made examples of, and ambushes to transport convoys, plain skirmishes and murder of personnel in the excavations and processing facilities being the norm. With their additional income being threatened, Madrid suspended citizen rights in the Basque Country and Navarre sending thousands of troops to assault as many ETA camps as they could. The Guardia Civil and ETA engaged in tit for tat clashes with millions of eurobucks in damage and hundreds of lives lost on both sides, many of them innocent.

The peak of escalation was reached when Madrid declared war against ETA and any Basque separatism. The King’s speech declaring war is remembered in infamy, filled with hatred, belittling, and contempt not only against ETA but the Basque culture as a whole. What little remained of the local autonomous government was dissolved and a military junta was established with loyalist commanders as the new leadership of the Basque country.

The response from the independence movement was swift. ETA and other separatist militias created a new self-declared government: the Euskadi’ free league. Aided by pirate stations blasting propaganda and the barrage of anti-Basque sentiments spewed by the Madrilenian government to the oppressed Basque people, thousands joined the league and became trained as fighters. Finally, with funding from Europa Sur, hidden support from Catalonian businesses looking to destabilize Madrid, and thousands joining their fight from the French basque country and other disenfranchised minorities, the league declared themselves independent and announced the Reconquista: A campaign to take the region from the government via force.

From then on assaults to take over cities, military bases and industries became the new normal for the Basque country; cities exchanging hands between the military junta and the league as they took from each other, with deaths and destruction piling up, and a no prisoners policy by both sides. Purges, roundups, informants and rewards for information became a common tactic from both sides to repress the smallest sign of rebellion. The civil war in the region has raged on nonstop and still continues. On one side the Euskadi’ league aided by eco-radicals and in the other the government forces joined by the Monteros de Espinosa. The north-east areas are mostly controlled by the military junta, while the western and southern areas are in the hands of the league.

Mariren seme alabak

Since the incident in Bermeo, eco-activism became more aggressive and violent. Spain, removing so many environmental protections, became a hotbed of the most radical factions. With the situation being as volatile as it was, the Guardia Civil did not take any risks and responded with bullets to the minimal sign of resistance. This did nothing more than worsen the situation and attract more radicals to Spain.

Most of it started with vandalism, but it steadily escalated to property destruction against mining and industries: Bombed transports, sabotaged machinery, and burnt warehouses. Then it went further to kidnapping of scientific teams and corporate and governmental officers, requesting closure of complexes in exchange for their liberation. From kidnappings it shifted to executions, videos of firing squads against corporate workers, from top executives all the way to the operational workers.

The biggest attack recorded happened in 2035 against the KNSM (Koninklijke Nederlandse Schildpad Maatschappij), a heavy industry corporation with steel manufacturing facilities in Navarre. The attacked industrial centre was the biggest of its kind in Europe, with over twenty thousand employees and a construction cost of passing 800 million eurobucks. It barely had a couple of years of operation when the assault happened.

The offensive was a highly coordinated operation, with multiple teams hitting from different fronts. A team of hired black operations techs and netrunners swiftly disabled security and communications and took control of command centres, experienced nomad packs took control and destroyed most access/escape points and sabotaged transport, and dozens of heavily armed militias suppressed the personnel operating the complex. The terrorists confined the crew, and with detailed knowledge bombed the precise points (fuel storage, furnaces, etc) to maximize the damage.

The whole affair was recorded and given to small medias with a recorded message by a group called Children of Mari, calling it “revenge for the desecration of the house of the mother”. The video was quite shocking, the skill shown by the group was only matched by their ruthlessness. Security and whoever resisted was swiftly and violently neutralized by the radicals, being immediately executed with Athames while declaring them enemies of the land. The ones who did not resist were quickly subdued, constantly insulted and beaten while being imprisoned wherever they could fit them. Right before the last stage of their plan, the leaders of the group made a passionate yet odd speech, identifying themselves as Anboto and Mundaka. They declared war to defend the children of the earth and the earth from the transgressors, declaring at the same time to act with goodwill and a wish to protect humankind, but still swearing the destruction of those who desecrate their mother. Following the speech, they detonated their explosives, fully demolishing sections of the factory and causing intense fires in the remaining sections. The laborers of the factory died, intentionally kept hostage inside, either crushed under rubble or in the fires. Several hundred people perished that night, and the facility was never recovered. The damage was so intensive that it was declared fully lost.

The Spanish government has been trying to fight against the zealots since the KNSM assault, but found themselves unable to achieve much. The group is quite hermetic and vertically structured, selectively recruit from other radical organizations after a long and careful study of the candidates. Information is heavily limited, each member works on a need-to-know basis, they operate in small cells, and their forces are highly trained and difficult to track. The Children of Mari are allied with many factions around Spain and Europe, as long as their interests align with theirs and against the corporations, although most of the time the alliances are quite loose. The organization is quite active and makes regular attacks, mostly against corporations, and is as pitiless as in the KNSM factory attack. Most of their attacks are sabotages and small scale skirmishes, but without fail, every few months, they execute bigger operations where the damage is in the scale of millions of eurobucks and the loss of lives easily goes over a dozen.

The organization is quite mysterious, and little is known about them. They do not seem to have any political or economic aim; they do not make demands, do not warn and produce little to no propaganda or message. The video recordings of their bigger undertakings is when most of their messaging happens, on them they normally add a speech rationalizing the action, critiquing the corporations for exploiting mother earth and warning others to not work for them and to correct their paths, that the mother is always forgiving for those that come back to her. It is suspected, although there is no confirmation of it, that there are towns and reclaimed cities where the trustworthy members train and discuss, deep in the outlands and the mountains.

Unlike other eco-terrorists who are more naturalistic, tend to be less cyber-modified and try to reduce collateral damage in their endeavors, the Children of Mari are less so. The end justify the means for them, so desecrating themselves, the land and the people is nothing but a cost for the ultimate goal. It is not rare to see heavily chromed solos and techs using, producing, and maintaining high-tech equipment in their ranks. It is also somewhat often that their operations cause small to medium scale ecological issues, and they do not shy away from the fact and are the first to admit so in their few recorded messages. Again, for them, the mother accepts a scratch if it is to cure the wound.

Next: Corporations and Europe