International Electric Corporation

There has been no corporation like IE, with such a wide reach and variety of production and verticals: From raw materials to finished goods, and with manufacture ranging from consumer goods, through military equipment to space technology. While most corporations tend to specialize in an area or set of products, IEC diversified across dozens of them. Although they certainly were a manufacture powerhouse, reducing them to just that would be a disservice, as they even expanded to media, banking, retail and services.

In the corporate landscape, IEC was uniquely situated by being a provider of critical parts for at least one product from the larger corporations. By ensuring their place as the sole supplier of relevant technologies, they established themselves at the core of many markets. With a size comparable to the biggest players, such as Arasaka, their influence and power could not be denied.

Their relationships with other corporations were unusual, staying from neutral to cordial even with standoffish corporations such as Arasaka but having little to no allies either. Most corporations made sure to maintain good relations with IEC, they were too large to be fought against and angering them might have risked embargoes and heavy economic consequences. Another reason for little conflict happening involving them is that they largely kept their distance from the markets of larger conglomerates, and especially those of the other fishes big enough to hurt them: Arasaka, Militech and EBM, instead profiting by providing critical components for their products. IEC vision was to grow, to become more profitable. They tried to avoid pointless politics and just focused all their energy on achieving their business, being ruthless in the process, but straight-forward and transactional.

When the 4th corporate war began, IEC’s position showed to be profitable, staying neutral while providing to all sides. Needing to produce and maintain tonnes of weaponry, both Arasaka and Militech reluctantly accepted the fact that they were doing business with a company providing their sworn enemies. By limiting the amount of inventory that Arasaka and Militech get sold, IEC ensures they must come back and therefore keep themselves on their good side.

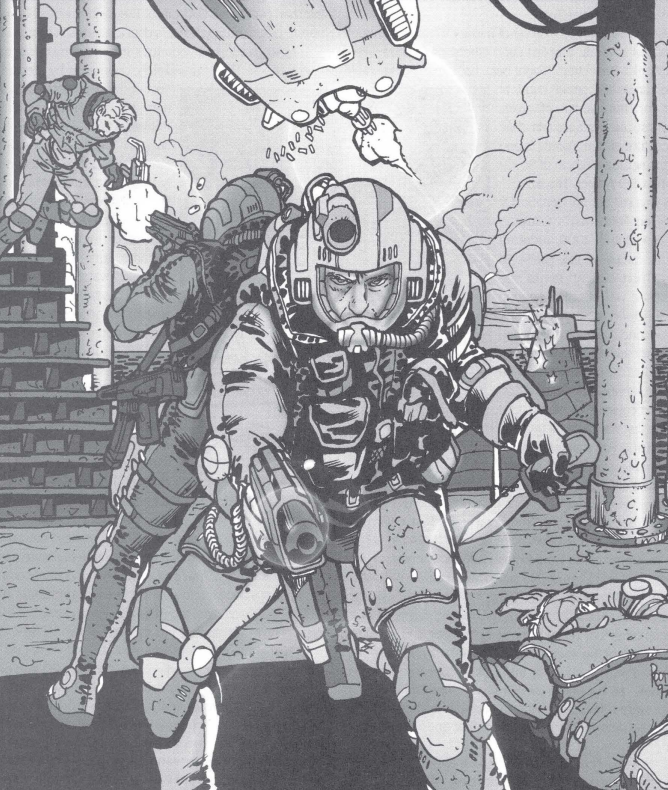

During the late stages of the shadow war, however, a series of black ops assaults occurred against Kessler North Atlantic Shipping (IE’s shipping subsidiary) cargo ships, and even to some of their famed submarine transports (A huge blow to their reputation as one of the safest cargo transportation methods). IEC, after investigating, determined that evidence shown that several of the attacks could be “reasonably suspected to have been made by Militech and/or Arasaka troops in an attempt to disrupt supply lines for their opponents”. Both Militech and Arasaka vehemently rejected the accusations, denying any responsibility, but with the trends during such times, it was unlikely that IEC could be convinced otherwise. As a result, IEC declared an embargo against both corporations. Even though Arasaka and Militech were not pleased, they made what they could of it and took the chance to exert pressure on IEC into both lifting the sanctions and keeping them towards their opponent. Worse case scenario, IEC would be no longer.

With little to lose from Militech and Arasaka, and the first signs of the hot war brewing, operations against IEC facilities became commonplace, with regular raids ending up with component cargoes being stolen. It began with mostly transport interception, but it quickly escalated to sabotage, assassination and eventually full blown assault or bombings of IE factories and hubs. Kessler and IEC tried to prepare for this scenario before the war started, stockpiling weapons and preparing troops. Nevertheless, there was no way they could have prepared to receive offensive from Arasaka’s immense corporate forces and Militech’s mercenary forces. While managing to keep most attacks off from their most critical manufacturing complexes, the damage done against IEC was incommensurable.

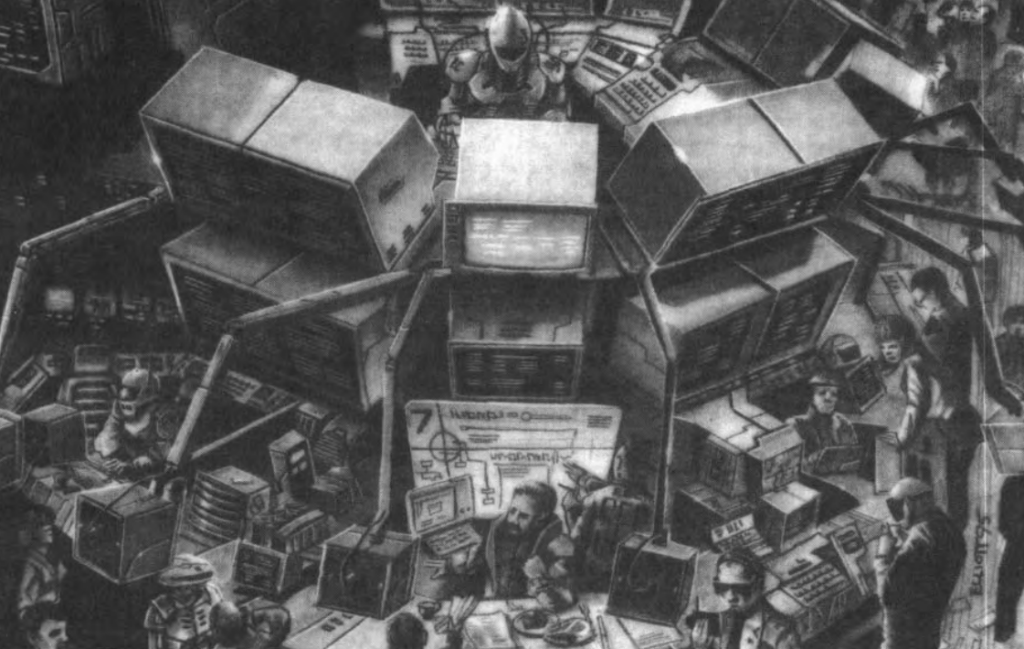

Between the loss of business from their embargoes, the destroyed and stolen goods, and sabotaged facilities, IEC financials did not paint a positive outlook. This, as expected, reflected poorly on their public valuation and stock market prices, but Kessler and the Berlin Industrial Investment Group loyalist control ensured no internal mutiny could happen. Control would become increasingly difficult to maintain for Kessler as waves of leaks made it into the public eye, with hundreds of internal documents and financial information publicized in the media and the extent of the damage made to them by the war becoming open knowledge. Investment funds and corporations shorted IEC positions in increasing numbers, up to a 140% of the public float being shorted.

Pressure mounted up from all fronts for Kessler and IEC. Income was on a downward trend for months as Arasaka and Militech did what they could to coerce IEC, and, as the short on their stocks tightened, investors became exasperated. Creditors also became scarce as firms became scared of interacting with any side of the war in fear of retaliation of the other side, and Eurobank, reading the scene correctly, knew any loans to IEC was a losing bet.

IEC saving grace came from a compatriot corporation, Euro Business Machines. EBM lent IEC millions of Eurodollars, helping them to keep operations, hoping for an eventual normalization. EBM’s help was unexpected, but being inoffensive to both Militech and Arasaka, they could afford to come into IEC’s support with little conflict. Also, with the combatants fighting on so many fronts and being very large themselves, the risk was manageable. It was unclear what EBM was aiming for, but their publicized reasoning was that IEC, being a provider for components of many EBM products, was critical for EBM, and it was in their best interest to forge a close relation and ensure their longevity. IEC was suspicious, but without allies and desperate, had to accept.

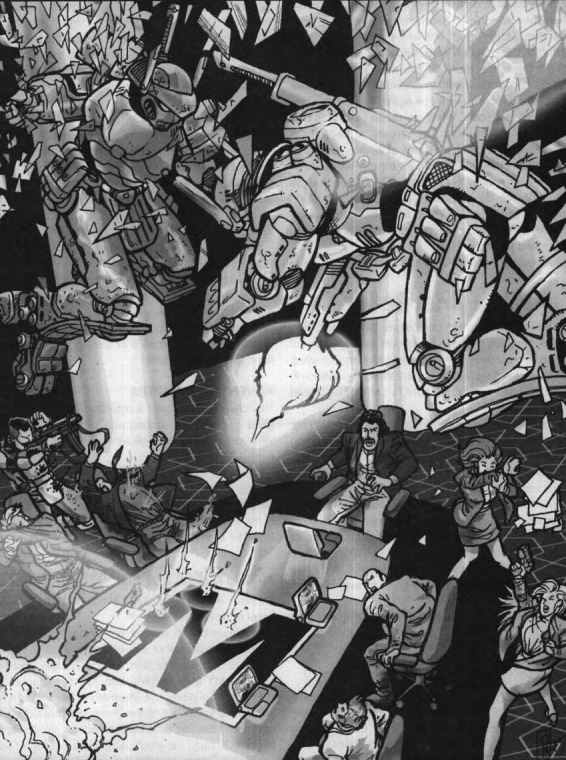

IEC’s future did not appear to shine, but seemed better now that EBM was helping them to pass through the storm. Unfortunately for them, it devolved for the worse. IEC had most of their corporate security forces stationed in their electronics manufacture facilities and related locations where those goods moved through, as a good number of the sabotages and assaults happened there as Militech and Arasaka tried to bypass their embargoes. They did not expect that one of the biggest operations would be launched against a IEC Raw materials division facility. A fleet of unmarked airships launched a huge bombing against the largest IEC ore processing complex near Perth, Australia. The attackers did not survive, being taken down by either the air defense systems from the factory or the Royal Australian air force, but they managed to damage a huge part of the plant.

To be already struggling, and to have then a huge profit loss from one of their heavy industries, while also losing the input for many of their other businesses (iron, copper and other metals) was the final blow on IEC. EBM, citing worries about the latest hit on IEC and the safety of their loans’ returns, retired their cash flow to the corporation. IEC had no other option but to declare bankruptcy.

As with any bankruptcy, IEC’s assets were taken or sold for the creditors, and EBM, being the largest secured creditor of IEC by large, had priority. However, the liquidator and EBM’s operated unusually. Instead of liquidating assets, EBM recovered their loan by retaining their collateral: assets and intellectual property over hundreds of electronics, technology components, some high-tech weapons technologies, the totality of the energy and space division of IEC, the cybernetics division, and electronic consumer products. The way the liquidation happened is suspicious to this day, instead of liquidating in public offer the valuable properties they were simply impounded and transferred. Such an acquisition transformed the nature of EBM permanently, making them the largest electronic manufacturer in the world and a foundation of the damaged corporate world of the post-war RED.

There is a theory, albeit unconfirmed, that the initial attacks to IEC that started the conflict with Arasaka and Militech, the leaks of internal information about IEC, and the Perth attack were all orchestrated by EBM in order to weaken IEC and acquire from them their properties and market, it is for sure not the first time that EBM would be involved in aggression like this. Whoever is responsible, however, managed to destroy a giant that, in its most profitable times, plundered and destroyed many others.

Euro Business Machines

An electronics giant, EBM is the largest manufacturer of computers and high-tech manufacturer in the world. The corporation provides not only consumer-grade computers and electronics but also business-quality servers, security systems, and even produced what was a good part of the infrastructure of the old net. They became even more relevant during the time of the Red, thanks to the fall of the net and their acquisition of IEC.

The fall of the net opened a new market to EBM to tap into, specially in their home continent, Europe. CitiNets and new infrastructure were needed to keep Europe functioning, and EBM quickly dominated and aggressively undercut anyone trying to enter their territory. Every major city CitiNet is managed by EBM, with EBM backbone, EBM terminals and EBM subsidiaries software; EBM manufactures the elements that form network architectures, from the servers to the access points and interfaces for control nodes and ships each machine with their EBM PIM (professional interactive management) systems. The foothold that EBM has over the computer systems market is unparalleled and the profits that come from it are extraordinary.

EBM’s hold over old IEC technologies and consumer goods made EBM much closer to what has always been their goal: consolidation of a lot of high-tech manufacture under their hood. EBM is now the main if not sole provider of electronic parts for military technology; consumer goods from kitchen appliances to advanced domotics; energy and communications machinery; and a vast amount of the circuitry, control systems, and lifting systems used for space technology.

EBM, with their experience, technology and resources, are an active participant in the research and work towards the Blackwall, working closely with Netwatch and Alt Cunningham. Their ruthlessness and intrigues are a worry, but they are surely spearheading the work towards the recovery of the net. It’s also suspected that EBM is working towards ways of communicating with transcendental sentience AIs, but the veracity of the rumor and the level of success is unknown. EBM research teams are continuously working towards new computers technology, lately specially on surveillance and more controlled but powerful AI technology, with fewer risks than the pre-datakrash times: complex enough to compete with the inhabitants of the old net but secure enough to be used without losing control over them.

Eurobank

The warrantor of the Eurodollar, and probably the largest financial institution worldwide, Eurobank is vital for everyday life all across the world. Not being a corporation but instead a public institution, their business operations are tied to the European government, and it shows in their way to operate. It’s a solid and dependable company, and very traditional. They lend funds to thousands of investments and corporations and are critical to business.

The 4th corporate war and the datakrash, however, tanked thousands of corporations and depressed the world economy. Eurobank suffered in the same way the economy did. Being the creditor of a multitude of failing businesses, Eurobank was inevitably hurt. Their management and the European diplomats, however, were not novices, and many of them weathered through the Crash of ’94, three corporate wars, and dozens of other crisis. With the power and control the European commission had, the governments and Brussels worked vigorously to maintain their economies afloat, leveraging to the maximum the world stock exchange and the common market they minimized the damage.

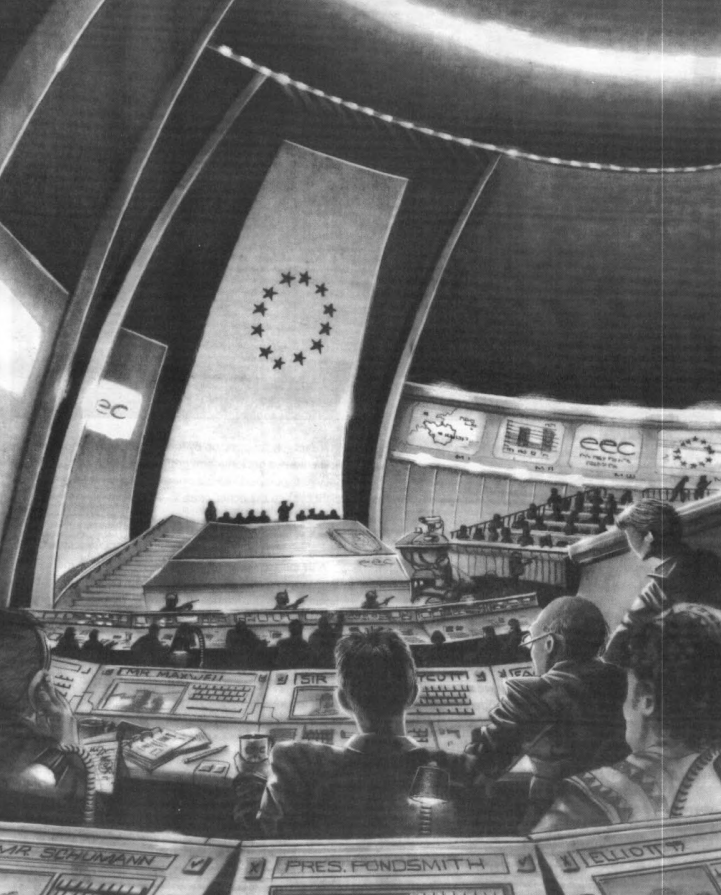

The datakrash was specially disastrous for Eurobank, making them lose decades’ worth of systems and records. Naturally the net was a core element of international banking, and recovering from its disappearance was a titanic task. The EC immediately took action, as not doing so would have been devastating for the world economy. A way to maintain both financial operations and international stock exchange was necessary, but even the core to create such a system in an international level was lacking, and the easiest but quite expensive way to ensure international communication was through satellite systems. A gigantic project was undertook immediately in collaboration between Eurobank, EBM, ESA, the European comms commission, and WorldSat CommNet.

Financial computer systems are, by design, very secure. With every actor being authenticated at every step, every action recorded and scrutinized, and every operation subjected to authorization protocols limiting what one can do to nothing more than one should. Add to the mix the risk of a destructive virus and AIs lurking in the very backbone of the system and security needs to be absolute. With the know-how of EBM, and working closely with technicians of the ESA and the Confederation, exclusive hardware and a fully airgapped system were created communicating main offices of Eurobank and a few selected corporations and institutions worldwide being carefully guarded by Europol, netwatch and intelligence agencies alike.

The technology and access to the Eurobank system is a highly guarded secret, using it requires access protocols akin to those used by intelligence forces with many layers of authentication, and fine-grain permissions carefully curated and constantly reviewed. The technology and protocols used to transfer the data through air are unknown and custom made for the system, and the terminals and access points to use it are outside of the access of any external actor. At least until now there haven’t been any known security breaches or information leaks about the project, information about it is very limited, and when the faintest detail gets exposed, the ones providing such data and the data itself get quashed and buried, very fast.

The system, coded project Yggdrasil, is unique to anything that exists during the time of the red, being one of the few ways where international communications happen. The system enables keeping the flow of money and financial services international, but also allows the stock exchange to function. It cannot be stated the amount of power and influence that project Yggdrasil gives to the EEC, having already the international fiat currency but adding now the control over the stock exchange, the European commission now has on their hands the world’s economy. Now, the system is not widely used as operating internationally via Yggdrasil is an expensive undertaking, so mainly elites use it in an intercontinental level.

Yggdrasil, as a platform for the stock market, was primarily a power grab by Eurobank and the EC over the local exchanges, becoming themselves the providers for many local markets, mainly in Europe, quoting “simplicity and unification of market trade”. The EC recommended local governments to disband their exchanges and let Eurobank operate them. That way, local operations and intercontinental operations could be handled seamlessly, and the delays from the Yggdrasil project security protocols would not put their national investors at a disadvantage of the rest of the members who could react to the markets much faster than they could. The ploy was successful, and many governments agreed.

The Milan Directive

October 18th, 2022, the date when the 4th corporate war ended in Europe. After a warning two days before that any other aggression would have as a result the nationalization of the two sides’ assets, when a Militech showroom was attacked in Milan, the EC immediately followed its word and mass nationalizations were done. Both sides insisted that neither had anything to do with the assault, but the commission did not budge. Not long after deliberations began on what would become the Milan Directive, or Directive 2023 – EC – F – 00098. This was, officially, a response to the destruction of the 4th corporate war, with the EC pledging to never allow a war such as the 4th corporate war to happen again.

The Milan directive created the new Business Transparency Commission (BTC), an offshoot of parts of the trade commission, the finance commission and the EDF. The commission comprises legions of accountants, auditors, investigators, spies, special forces, intelligence officials, and many others whose job is to keep tabs on corporations who are becoming too open in their side biddings, or that are stepping into the EC’s toes too much. The military power of the commission is comparable to that of the Europol, not by numbers, but for the expertise of their forces. However, the BTC’s might is not one of force but of knowledge. Once a corporation gets into the commission’s radar, their auditors and investigators would analyze every single submitted record your company haves for any sign of wrongdoing. If they find any, their spies and investigators will discreetly infiltrate the company, find all the evidence they would need and the weight of the BTC would then fall onto the corporation. If the instigator resists or plans operations considered too dangerous, the BTC’s special forces would swiftly shut your operation down with all the force they have available.

The directive also defined the allowed behaviours for corporations, the face role was created, and arbitration and remedies were established. In a nutshell, the document defines that illegal activities, such as industrial espionage, sabotage, kidnapping, and many others that result in damages and can be effectively pointed to be caused by a corporation intending to harm or instigate another would cause punishments to said corporation or their face, with varying degrees of gravity. The arbitration methods defined are mostly a formality, as the commission has almost no oversight and, when they decide to prosecute you, it means they have enough evidence, real or fabricated, to take you.

The Milan Directive most interesting clauses defined what would be the remedies for the crimes the corporations committed. The details are many and complicated, as in any document made by the EC, but in short, the remedies were defined as follows (loosely ordered depending on the gravity of the transgression and in cases of re-offense):

- When damages to property or life to an opposing corporation are proven, the offender will be issued fines based on the damage against the opposite corporation (excluding the cost for the damages done, those should be pursued civilly by the opposing party) and those found directly responsible will be prosecuted and jailed

- When the damage to property is major, is done to government owned property or heavily impacts the public, the culprit will receive major fines based on income percentages

- Public exposure of the corporation crimes. Forced and publicized apology by the corporation’s face

- Increased scrutiny and regulation to repeated lawbreakers. Initially, this means in house auditors having access to any document or information they request, but can escalate from recorded communications, higher bars of perusal to permits, to even operations and expenditure needing approval by government representatives

- Financial sanctions: Suspension of financial trade, limitation of access to public contracts, reduced or removed access to Eurobank credit

- Forced removal of officers, board members or the face

- Forced requisition, sale of assets, and to offenders who get uncomfortably close to causing another corporate war, nationalization

The stick would not be complete without a carrot on it. So there are also ways to clear the records and improve the corporation standing with the BTC, as long as the crimes committed are not too egregious. This can be charity, unpaid government work, retribution to the affected parties with little resistance and litigation, or simple good behaviour.

Now, in reality, the corporate landscape in Europe hasn’t changed too much since 2020 times in Europe. The European Commission did create the Milan directive with the intent to avoid another corporate war that would damage the community as the 4th corporate war did, and to put under control the barons becoming too open in their violence or opposing too heavily to the government, but the document was mostly for show, to give the appearance to the population that the EC was strong against corporations putting in danger their way of life. Do not mistake the existence of the directive with accountability to corporations or equal prosecution. The lack of oversight of the commission was not a mistake. As long as infractions are not too big, cannot be traced back to you, and do not go against the interest of the wealthy and the well-connected the commission will not be interested, they have plenty work already, a few unemployed or blue-collar workers sick or killed are of no concern to them. Remember that many corporations are tied to goldenkids, influential families, and EC diplomats. The more bureaucrats you know, the more will be forgiven and forgotten, the lower you are in the food chain, expect more consequences, and less fairness. Keep your head down, your plausible deniability high, do not speak too loud against the commission and your local government, and you should not have any encounters with the BTC.

Next: France