The food shortages

France was a country with a perennial food excess. Having their small family-owned farms, inefficient but loved by the people, they kept more than enough food for their people, with a comfortable surplus. France has rejected, by law, to allow large corporate farms to even exist, fighting fiercely against not only the corporations themselves, but Brussels nudges to allow big business to run in their country. Food is a core element of French society. Food is a moment to be shared, business and discussions get decided over a meal and a cup of wine, and the locals adore and preserve traditional and regional foods. Noone would have believed that France would find itself having food shortages.

The 4th corporate war and the early postwar years were unkind to the farmers, with the rural areas imbued with violence, millions of Eurodollars in equipment and crops were stolen and destroyed. The rural towns pleaded with the government for protection and help, and their government tried to, but it was an impossible task to properly protect such a vast country with the level of unrest it had. An exhausted police force that just left behind a war was finding itself fighting a new one against their own desperate people.

Initially, the shortages were small, a bit of produce missing here and there, having to walk to some out of the way store or vendit, a couple of days of missing stock. But, as the datakrash impact became stronger, it devolved to weeks of products being unavailable, expensive food and some items gone from the shelves altogether. The unemployed had the brunt of it. Unable to feed themselves, with their supplies reducing, they were pushed to crime for survival, exacerbating the country’s delicate situation. With the police forces weakened, tied up and spread thin trying to maintain order, farms kept being ransacked, which, in turn, worsened the shortages, pushing more people into desperation.

As the weeks passed and the extent and impact of the shortages became more evident, tensions ran high throughout France, and protests began to occur. First, it was mostly the farmers pleading for help and protection for their lands, then it was the unemployed begging for more rations, followed by industry workers who were finding it difficult to secure meals as prices rose sharply. Then a few protests turned into riots, radical groups clashed with the Gendarmerie, and looting and vandalism became common. Finally, arrest, beatings, Molotov cocktails, pipe bombs, rock throwing, tear gas, rubber bullets and broken glasses were the rule in the French cities at least a few times a week for several months.

After a long and criticized deliberation, the French government finally put into a referendum a support package for the French agricultural industry. The bill started truly generous, offering large amounts of resources to the affected farmers, not only to hire security for their lands but also to help them survive the season and restock their lost tools and materials, and it all came as grants. However, the European Commission strongly protested the bill on the grounds of it unfairly favoring French businesses, rewarding inefficiency and reversing liberalisation. Brussels also reminded the government that “in such uncertain and trying times it would be wiser for them to be austere and efficiently allocate their resources”. To the people’s discontent, the government capitulated to the EC and reduced the allocation of funds, also converting a good portion of it into loans instead of grants. Nevertheless, the vote over the measures comfortably passed.

The act’s intervention was sufficient to prevent food scarcity from worsening, but not enough to remove it altogether. Not only the money was not enough, but haste makes waste. Part of the reason behind the decision of reducing the financial allocation for the law was to more granularly allocate capital to where it was needed, but this did not happen, and the reach that could have been achieved was severely undercut. Between the need to act promptly, the distribution issues of the time, the violence, and just good-old inefficiency, a considerable portion of the money was either misused or lost. Regardless, the passing of the measures was a remarkable and celebratory event, with praise raining for the government and their response to the crisis, advertised as meticulous and noble. A disconnect was forming among the French population, those who believed that their government, even if not doing the best possible, acted reasonably and those who saw the government response as submission to Brussels and to be wholly insufficient, nothing more than a patch over a deteriorating situation.

Most of the media and the political analysts had hoped that the measures would cool down the riots and protests, but unsurprisingly to those on the ground, it did not. Those that considered the government response inadequate were, as to be foreseen, mostly those who protested, and they wanted a return to normalcy, not barely surviving. If anything, the law just made the more radical factions to become enraged, decrying the solution symbolic at best. However, a tired and, some might say by design, apathetic population became annoyed with the protests and the price in their daily lives. Transport interruptions, section of cities quartered or inaccessible because of the clashes, deterioration of their neighborhoods, and lost or destroyed business quickly dwindled support for the protestors’ cause. A lack of information, a surgically planned propaganda machine and an overwhelmed population made the French people to stop supporting their own protesters, considering them a nuisance, or even terrorists.

As some say: “When it rains it pours”, and France was not out of the woods yet. The farmers that survived the violence, indebted and barely making ends meet, were now facing the environmental effects of the war, and the pollution from the repatriation of industry. Erratic weather patterns, iron poisoning, and contaminated soils, water and air did incommensurable damage to land and vegetation alike. Despite most of the crops grown worldwide being modified strains prepared to survive unstable environments and some levels of pollution, what was available was plainly not good enough. Shipments of produce had to be destroyed because of dangerous levels of contaminants in them; some crops’ growth was inhibited, severely reducing production; entire seasons’ worth of food did not survive; and, in some places, fields became so damaged that they turned unusable without some serious intervention. It has been a long time since such lack of food access was seen in a core European country. No one expected such a dire state of food security in a country like France. Now, it was not only the unemployed having issues to secure food on a regular basis, but even up to low-middle-class citizens. It never came to the point of citizens starving, but it was a serious reduction to the working class living standards. The unemployed were finding themselves having fewer meals available per day (meals being terrible kibble to begin with), while the rest had to either drastically reduce food quality and nutrition (to either poor quality prepaks or kibble) or even lose meals altogether, both because of unavailability and rising costs.

It was now or never for the French government, and if they did not want to find themselves with a revolution in their hands, they needed to act fast. On one side, riots were worsening, and public approval was deteriorating quickly, so they needed large and decisive action to quell their people’s indignation. On the other, Brussels kept calling for more efficient and cheap solutions, such as large-scale farming. Regardless of their choice, conflict was bound to happen. The Chamber of Delegates was hung in deliberation for weeks, with each side pushing for their ideas but unable to pull enough support from the other to finalize any bill. Weeks passed and people wanted a solution or wanted them out.

And the final blow finally landed. In the very heat of the debates, the screamsheet La Suzanne published a huge corruption expose on dozens of delegates, linking them to abuses during the first round of support packages to agribusiness. The report unearthed evidence showing grants being funneled to farms affiliated to representatives, specially delegates from the agricultural regions, and invitations to tender for equipment and services being granted to companies with lobbying ties to government officials as high as the prime minister. A scandal on this scale would have been devastating during the best of times, while facing food shortages, it was the start of a new republic.

The second Bastille Day

July 14 was the date selected for what the organizers called “the people’s council”, where it was estimated that three million demonstrators took part in the biggest mobilization ever seen in Paris. The protest was a diverse and charming array of people and expression: artists painting and composing, creating murals, improvising music and poetry; activists and politicians debating and giving speeches; communities uniting to help and discuss their issues, offering their know-how in trade to each other; protests, chants, congresses and petitions being made in front of government buildings; and walks all around Paris expressing their discontent with the government.

Demonstrations were, for the most part, peaceful. It is unknown to this day from where and how the violence started, but clashes between police, protestors and rioters appeared and increased in hostility. Thousands of protesters were arrested, hundreds were injured, and dozens of both demonstrators and police forces died among the clashes. The biggest and most deadly of all the events of the day came after representatives of some of the organizing groups (worker unions, activists, people’s right movements) called for a walk to the Palais Bourbon, house of the Chamber of Delegates. The Gendarmerie, spread around the city fighting rioters and patrolling rallies, was afraid of a revolt too close to the government, so, citing safety concerns, did not allow activists to get closer than several blocks aways from the chamber. Most marchers complied, but with the environment of the post-war France, it was destined to become bloody.

Enraged and exhausted with months of struggle, many protesters decided they had enough of letting the government step over them. Take the poorest workers, having barely enough to live and feed themselves, facing months of increasing scarcity, in the middle of the post-war economic crisis, tired of listening through the vid that what they were facing had no solution, and they just needed to hang on. Imagine them constantly hearing that their dissent, their movement, was an annoyance with no reason, no logic nor aim, while politicians robbed them of their money. Picture these people, filled with anger, disenfranchisement and desperation in the middle of the heat of the protest, surrounded by those that have the same rage they had. They needed a solution, or at least an escape. Think of the unemployed, disenfranchised, hungry, without an escape, powerless, being finally heard, if not by the politicians, at least by their peers. They lied dormant thanks to decades of propaganda, giving up to the corporations, to the elites; they wanted to do something; they wanted change; they wanted July 14th to be forgotten as the Bastille Day and instead to be remembered as the birth of the 8th republic.

The march became riot not long after arriving at the barricades around the Palais Bourbon, with confrontations between the Gendarmerie and the protesters, but as the news spread around the city, more people became emboldened and clashed with the police, attacked governmental buildings all around Paris, and escalated their dissent into revolt. Paris was not unfamiliar with riots, and was a witness of all the new republics and their costs, but this one was one of the biggest revolutions Paris saw in its time. Injuries, arrests and death were the rule of the day, and millions of Eurodollars in property were lost on that day.

The confrontations around the Palais raged for hours. On one side the rioters, with those in the front armored with industrial protective equipment and makeshift shields, on the other the Gendarmerie’s riot police. The first throwing rocks, glass, paint, makeshift explosives and slinging back tear gas while the others shot flashbangs, pepper spray, rubber bullets and mace while trying to hold their ranks against the barrage from the rioters. Inside the building, the chamber of representatives raged in a war of their own, gathering in an emergency meeting thought to discuss the food crisis that instead devolved into screaming matches, insults and fistfights about the corruption scandal, the crisis and the riots outside. The vid news channels were a dystopian sight, on one side what looked to be heavy industry workers battling against the police and in the other well-dressed politicians, unaccustomed to fighting, struggling to throw punches at each other.

During the first hours, it looked like the attackers would not be capable of budging the line of police. Experienced as they were, and with what was in the line, the gendarmes repelled assault after assault from the rioters. But the revolters did not surrender or stop. By sheer force of numbers, fueled by anger, and with the background of the more hardened of their activists, the fighters carried on. They had rotations of people, flanked the police, produced equipment and weapons, brought supplies from the worker alliances, and just kept pushing the police. Spread around the city and without backup, the rioters chipped away the police’s energy, who slowly but steadily had to retreat and give ground to the demonstrators. Inside of the chamber, the knowledge of the marchers being a few blocks away, the imminency of the ultimate explosion of the corruption scandal, and the inability to secure a solution to the food scarcity was heating the debates up to a boiling point. Nothing productive was being done, just yelling and quarreling.

After three hours, the rioters had gained several blocks, being as close as ten blocks away on some fronts. The French army was called for support, but the government was unwilling to use lethal force to combat the protestors, fully aware of the backlash they would receive. Having the army on the streets was dangerous enough. The insurgent’s spirits were high, gaining street after street, hearing about their comrades’ victories. There was no other path than to keep pushing. Victory, whatever that meant, was close. The perimeter kept becoming smaller, eight blocks, then five blocks. It became clear that the delegates had to be evacuated. Teams of special forces, corporate solos, and elite teams were called in from all around to take that small army of politicians, it’s not a simple task to securely extract 800 delegates plus their teams.

The demonstrators had won; the politicians fled. They pushed what little remained of the police forces who, defeated and beaten, pulled out, giving a path for them to finally enter the Palais. Several hundreds of the protestors entered the chamber where the delegates met and held a session of their own. They then read a powerful manifesto, stating their concerns, expressing their anger, and voicing their silence. They called the government useless, arguing that they no longer represented the French people, but instead themselves, their cronies’ interests, and Brussels. They called for their resignation, for a new constitution, a new state, one that would truly represent what the citizens believed was the best for the country, instead of aimlessly nodding or negating in pointless referendums. They proclaimed the creation of a new party, the yellow helmet movement, one that would be there, policing the politicians, fighting against their abuse, rising whenever they acted against the public interest once more.

The 8th Republic

The aftermath of the corruption scandal and the riots came swiftly for the French state. The government was dissolved and an emergency one was created, tasked with creating the new constitution. The new interim assembly was made of representatives of important sectors of the French population and industry: worker unions, business federations, academics, technocrats, and corporations. Debates were fruitful and interesting, with many reform ideas, ways to make the government more accountable, and innovative forms of leadership.

But amongst them all there was a radical and fascinating idea speedily gaining strength, taking support from the worker unions, academics and technocrats alike. It was called Futarchy. Proposed by technocrat Satoshi Dutoit, founder of the company managing the French elections system, it attracted attention with its catchy slogan: Vote values, but bet beliefs. Dutoit’s idea was that, when a problem needs solving, experts from interested groups would meet and propose a set of solutions. Say, for example, the food shortages crisis. Agribusiness entrepreneurs and economists would meet and design policy programs for the issue. For our case, the plans could be the allocation of funds to the farmers, with different levels of capital injected on one side, and in the other could be instead limited support with additional grants pushing for modernization and automation of the grantee’s business. The panel would then choose a benchmark, a way to measure the success of the measure, say billions of Eurodollars in business. Per project offered, you’d then open a market with a single ticker, where that stock would pay an Eurodollar per billion of business produced after a maturation time, for example 10 years. The idea of using markets is that those who are interested or knowledgeable on the program and its effectiveness would put their money in what they believe is going to result from the measure taken. The markets for each proposal would run for a few weeks, and whatever market ends up with the higher average price would then be chosen as the approach to be implemented. The other markets get refunded, and the one accepted keeps running until the maturity time passes. Then those holding positions on the market would pay or be paid depending on the actual results of the benchmark.

The system sounded ideal, one where those knowledgeable created the solutions and those with information and interest enough would put their money in, leaving no space for corruption and cronyism, in theory at least. Even if the experts would try to push a policy when paid or pushed by interests, the markets would vote it out. Also, being invested in the bid, those acquiring positions would need to believe that the strategy where they were putting their money would be, indeed, successful, otherwise, they would lose their own investment. Third, the belief was that, if a plan had a higher price, that should translate to informed investors predicting that the law chosen would bring the highest returns of them all, and therefore the best results to the public. Last, and of most importance to some, futarchy was a system with essence and charisma, unique, putting France at the edge of politics. Public support for it was through the roof, and after some drafting and negotiating, the emergency government agreed, approved it and wrote it into law. The 8th republic was born.

A trial by fire

The premiere for the new system was nothing short of crucial: solving the food shortages. Being a contentious affair, making the proposals proved exhausting, and having the load of proving the new republic added pressure for sure. After two months of deliberations, drafts, and back and forth, the propositions got published. The first was a comprehensive package of public funding, with a detailed allotment of resources, guidelines, and training. A second submission, more in between government intervention and markets, suggested opening the French agriculture to larger corporate farming, and, in order to keep the local farmers capable of competing, investing the tax revenue from the corporations to the local smaller farms. The third and last plan presented an economy of scale solution to the issue, allowing larger and leaner agricultural businesses to exist in France, attracting the investment of corporations, and producing more for less. The metric to be used was a complex formula joining a collection of measures, core in them being the agribusiness revenue and the amount of food produced.

The markets opened, and public opinion was very divided. The population was quite protective of their independent farmers, but were also resentful at some of them for their participation in the corruption scandal, and also fed up with the shortages altogether. Those more vocal on their rejection of corporate farming tried to move the markets towards their position, campaigning about the value of keeping their food out of the hands of the corporations. It was, however, difficult to compete against the clear profitability and effectiveness of the other schemes, at least at face value. There was a political and symbolic value in keeping the farming businesses in the hands of the small local family businesses, but not an economic one. The markets remained open for a month, with an immense amount of activity: shorting runs on one side and the other, buy and sell offers flooding the proposals. The excitement of being part of the first market of the French futarchy, and the controversy of the matter exploded the trade.

But, at the end, the markets spoke, and to the dissatisfaction of many, opening the French territory to larger corporate farming won. And in retrospective, there was no other way. At an objective level, the plan was the best way to solve the shortages, create a boost of agribusiness and create value altogether. But to the farmers, to those who loved to get produce and goods from their local farmers, to those who, on principle, rejected corporate participation in agriculture, a lot was lost.

Moreover, the game was rigged from the start. Intentionally or not, corporations and large investment firms had a lot to win and very little to lose by pushing for the opening of the French lands to corporate investment. They could aggressively invest, even at risk of small losses, for the proposal to deregulate the French markets while shorting the other two. If the corporations purchased positions at a realistic price, or even at a higher than market price, they were bound to gain either from the positions themselves or by their investments in the companies that were in line to win from the bill being passed (agriculture, biotechnology, agrotech). Shorting the other ideas, or purchasing at a lower price, was also mostly risk free for them. For the metrics chosen, the effectiveness predictions for the two other policies were clearly lower, prices inflated by political ideology or campaigns. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

A well oiled machine

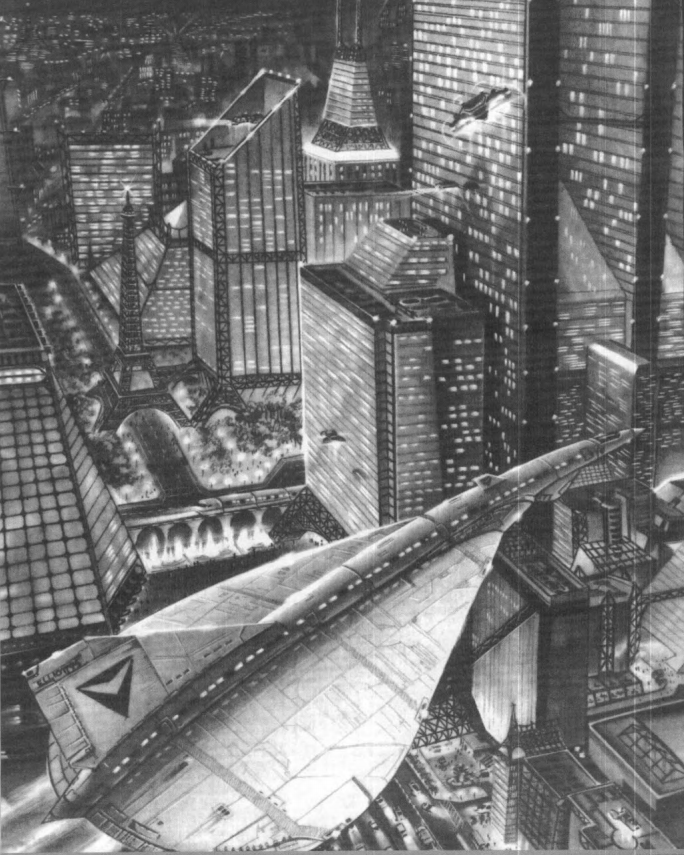

The 8th republic was a time of plenty for France. From all the EEC members, they had the biggest and fastest recovery. Led by experts, with every decision made with prediction markets, France developed nonstop in every measurement they voted to improve. Industry and manufacturing skyrocketed, energy production as well (although there are still brownouts and blackouts); business was booming. There are sometimes a dozen markets at a time, with proposals for every aspect of public life. Businesses and corporations flourished around the prediction markets: investment funds, consultancy firms, technology and software to operate the market, even betting around the markets.

But futarchy was not a boost for everyone. Progress has a cost, and the growth from the 8th republic brought was not free of casualties. The very measures to alleviate the food shortages took with it hundreds of small farms and businesses. Being extremely hurt, operating at a loss and indebted, many farmers had no other option than to sell their lands to corporations looking to create mega-farms for fractions of the actual cost, and either leave to the cities or become workers in what used to be their lands. Depression, both economic and mental, is part of life in rural France. The cost is not limited to the towns either, workers in the cities get laid off or become obsolete during modernization or offshoring drives. The line of those left behind just keeps getting longer and longer.

At the beginning, retail traders were eager and often took part in the decision markets. However, as time went by, business saw the potential for gain, and technology and experience flew in. Warring against large firms with deep pockets, more aggressive, better equipped and better informed, quickly leaves you bankrupt. There are some success stories, but most citizens lose money, and so less and less retail money flows on the markets and more corporate money chooses. That does not mean that corporations can get away with voting against the popular interest, or at least not often. If they try, other firms will eat them for profit.

Regardless, France is on the high, the fastest growing nation in the EEC, progress and growth all around, opulence, consumption, and pride. There is no need to even invest, the markets know better, and the investors will brutalize each other over each policy proposal. There is no need to care, they will choose what is best. As long as you are not part of the price, there is no problem too big for France. Nobody knows how long the 8th republic will carry on, when the next uprising will happen. Will the edge of society become large enough to fight back? Will their peers cheer for them as they did in the beginning of the republic, or will they fight against them? Will the markets once again vote, with no fanfare, lean and clean, to fix them.